In Ostia, an ancient harbour city situated around 20 miles South West of Rome, there are the remains of a 1st century bath-house known as the Baths of the Cisiarii. The name comes from the mosaic in the frigidarium – a large, cold pool that would have been used after the bather had visited the hot and warm pools. In it, arranged around the four edges of a pictorial city wall, are lightweight, two-wheeled vehicles that were the Roman equivalent of Victorian England’s hansom carriages.

Like the hansom, these vehicles – known as a cisium – were driven by a cisiarious, a driver who could be hired to take passengers on relatively short, swift journeys. They could be found around most city gates, and their speed was highly reputed and spoken of in many texts. For example, the Roman lawyer Cicero, in his first major litigation, spoke of how the news of Roscius the Elder’s death crossed the approximately 58 miles between Rome and his home town of Ameria in just 10 hours. That is not excessively quick, perhaps, but for comparison modern day endurance riding allows 12 hours to complete a 50 mile ride.

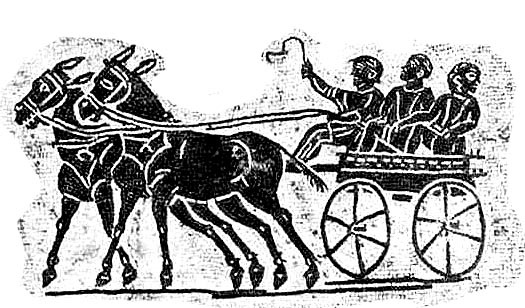

Mules pulling a cisium.

Mules pulling a cisium.

So it is interesting to me that the cisia depicted in the mosaic are drawn by mules – an animal who is better known for their endurance rather than their speed. The Ancient Greeks used mules in harness racing, and the Romans had a special chariot race for mules (as an aside: chariot racing with horses saw teams of two and four, whereas the mule racing only featured teams of two. Perhaps a team of four mules was more unwieldy?!), so it seems as though they were breeding good, fast hybrids. Pliny states that, “They are produced by a union between the mare and the domestic ass; they are swift, and have

extremely hard feet”.

The most fascinating thing about the Cisiarii mosaic, however, is that the mules are named! Inscribed in the tiles beside them are a fantasically weird collection of monikers: Pudes (Modest), Podagrosus (Lame), Barosus (Dainty) and Potiscus (Tipsy). Barosus, I imagine, was probably a delicate, high-stepping little thing. Podagrosus and Potiscus were perhaps not the healthiest of mules, and as for Pudes – perhaps he or she was an ancient Marty, shy and introverted?

Pudes and Podagrosus.

Pudes and Podagrosus.

When I first started looking into how individual mules feature in the history of the world, I assumed it would be a tough search because surely they are not as prominent as the horse. Finding named horses in history, myth and legend is an easy task, but would anyone have taken the time to consign their humble beast of burden to the annals of history? Duldul and the lesser known Fiddah were an early surprise – although as the favoured mounts of a prophet, they were hardly humble! So what prompted these ancient mosaicists to record the names of the four working animals? And are they the earliest named mules?

Throughout the Rome, mules were popular because of their strength, endurance, and steadier nature. Carts were a very common form of transportation and the city of Rome had laws that actually banned them from the streets during the day, so as not to clog the thoroughfares. Unfortunately this meant that it got very noisy at night – I can imagine that the mules added to this in their own unique way!

A rather charming 1st century mule head, carved in marble.

A rather charming 1st century mule head, carved in marble.

Emperor Vespasian was nicknamed “Mulio” (Muleteer) after financial difficulties forced him to start trading mules in an attempt to revive his fortune. There is a story that involves a wily muleteer stopping the Emperor’s train under the pretense of needing to shoe a mule, but Vespasian suspected that it was done to allow a friend of the muleteer to approach and discuss a law-suit. He asked how much the muleteer charged to shoe a mule, and demanded that he be paid half.

Vespasian is not the only leader to be associated with mules and their shoes: Emperor Nero was said to have shod his mules with silver shoes, and Empress Poppaea was said to have shod hers with gold.

Mules do well barefoot because their hooves are usually very strong, although some modern day packers shoe them due to the long distances traveled through very rocky country. As with horses, it depends on the mule and the terrain. In Ancient Rome, horseshoes were rarely nailed on. The Romans favoured the soleae Sparteae and the soleae ferreae (hipposandal), the former of which was a type of leather hoofboot and the latter of which featured studded iron soles. Both were fastened to the hoof with clips and laces. What we now recognise as a horseshoe was first created in Celtic Britain and Ancient Gaul, and adapted by the Romans. In the 19th century, a pair of iron horseshoes were unearthed from Pompeii – although their narrow gauge suggests that they were probably muleshoes!

A 1st century coin, possibly associated with Vespasian’s daughter Domitilla.

A 1st century coin, possibly associated with Vespasian’s daughter Domitilla.

My personal interest lies in the history of ancient Britain, so I was pleased to discover some mule-related insight into the Roman occupation. Rome introduced the donkey to Britain in 43AD, and equine bone evidence from Hadrian’s Wall suggests that our early British mules were much smaller than those found on the continent – just like today! This was probably because the animals being used for breeding were the small, native ponies. However, mules were not numerous. Britain’s climate did not suit the donkey, and it was expensive to transport animals to the island for breeding purposes. It was far easier and cheaper to utilise the native ponies instead.

The earliest record of the mule in Britain was a 2nd century jawbone discovered in London. Although the find is not complete, it is believed that the mule was certainly over five years of age and probably no older than mid-teens. Sadly, an area of the underside of the jaw that exhibits pressure atrophy suggests that this little Roman mule suffered harsh handling during its life – perhaps by a too-tight halter or muzzle.

Although the mule was uncommon in Britain before the 18th century, it is clear that they played an important role here during the Roman era. There is even mention of a specialist “mule physician”, found on a shard of cinerary urn unearthed in Buckinghamshire!