Back in 2016, I came across a poem called “Absence, or a record of the creation of a fabulous animal” by Gisela Kraft. Towards the end are two lines which read:

on the fourteenth they called you into the fieldduldul, ali’s tireless gray mule

Naturally, this intrigued me! Who was Duldul, to be named this way? Who was Ali? I set off on a fun few days of research, and learned that Duldul was the favoured mule of the prophet Muhammad – the “first mule seen in Islam”. Ali was Muhammad’s son-in-law, who looked after Duldul in her later years. I wrote up my extremely amateur findings here, just for fun (you’ll note that the reason it took me so long to find the poem again is because I had completely misremembered the line!).

In December last year, I received a message from a really nice guy who had read the blog all the way from Kurdistan. His name was Herish, and he had a really fascinating piece of local folklore involving Duldul that he wanted to share with me. Herish gave me permission to share the story myself, and asked that I take care to recount his tale correctly – so with the exception of punctuation (this was given to me as a series of Facebook messages), I have quoted him exactly:

My grandfather was a horseman, from an area called “Barwari Bala” . He once told me a myth about a horse animal named “Dildil”;winged, smaller than a stallion, larger than a donkey. He said the old ones said that on a time a prophet had a battle on a cliff called “Mozalan” land. The prophet was riding Dildil, he got surrounded and the cliff was on his back – Dildil could climb that cliff by sticking his hoofs on the cliff. [My grandfather] told me there are still Dildil hoofs steps on that cliff until this day. I know where that cliff is, but sadly I never went there to see the hoof steps. By the way, Dildil hoofs are not like horse or mule hoofs – they’re more like an elk hoof.

Herish also said that there is a folksong which mentions Duldul in the lyrics. At 02:15, there is the line “Atman sîyarê Dildilê yadê u yabo Atmana Pajo, here Mîsilê, bî mêhvanê cav kilê yadê u yabo Atmana” which Herish translated for me as:

Atman: is name. A hero name

Sîyarê Dildilê: the rider of Dildil, but Ê letter on the end of a name feminines it and whenever I heard about Dildil [it’s as a] male creature

Yadê u yabo Atmana: is like calling mum and dad. He’s Atman

Pajo: is like driving a horse

Here Mîsilê: ‘go to Mosul’, Mosul is a city in northern Iraq.

Bî mêhvanê cav kilê: ‘and will be a guest to the shade-eyed one’, talking about a lady with noticeable eyeliner that Atman will be her guest when he rides or probably flies, since it’s Dildil he’s riding to Musol

You can listen to the song below. It’s a lot of fun – Herish said it’s mostly sung at weddings, and has a special dance to go with it. He sent me a video of the dance being performed but unfortunately it’s a Facebook video, and I can’t figure out how to share it.

This was honestly one of the best messages I’ve ever had through this blog. I adore folklore, and the story that Herish shared with me is the best kind – I haven’t been able to find any other sources, so it seems to me that this is a very local legend and possibly one that is only remembered by a few. Escaping danger by dexterously scaling a cliff does sound like a very mule thing to do and lends credibility to the story!

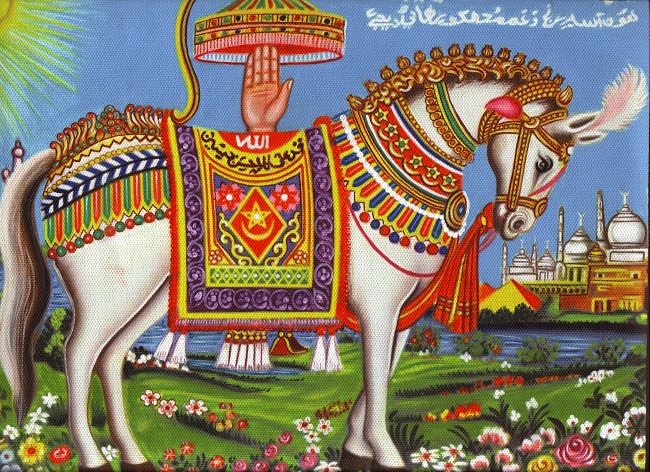

The description Herish’s grandfather gave of Duldul, and the line in the folksong, is interesting; while reading about Duldul I found that she was often associated with a creature named the Buraq – in some cases the Buraq and Duldul seemed to be interchangeable. I am not sure if this is part of Islamic lore or if there are just a lot of people as confused as I am about the identities of these two creatures.

In relation to this topic, the parts of the Buraq’s legend that are interesting is that he is a male creature*. The Sahih al-Bukhari (one of the six major hadith collections) describes the Buraq as “a white animal which was smaller than a mule and bigger than a donkey”. Certainly sounds like a familiar description, doesn’t it?

* Although first century scholar Ibn Sa’d has the angel Gabriel refer to the Buraq as female, and who are we to argue with an archangel?

One of my favourite references to the Buraq – and one that backs up the notion that he may be a derivative of Duldul the mule – is a story that tells how he bucked the first time Muhammad got on him. Gabriel, who is apparently well-versed in the ways of mules, places a weary hand upon the Buraq’s mane and calmly asks, “Are you not ashamed, O Buraq?” The Buraq was ashamed, and this prompted him to sweat profusely before standing quietly and allowing the prophet to mount. I think I might try that with Marty.

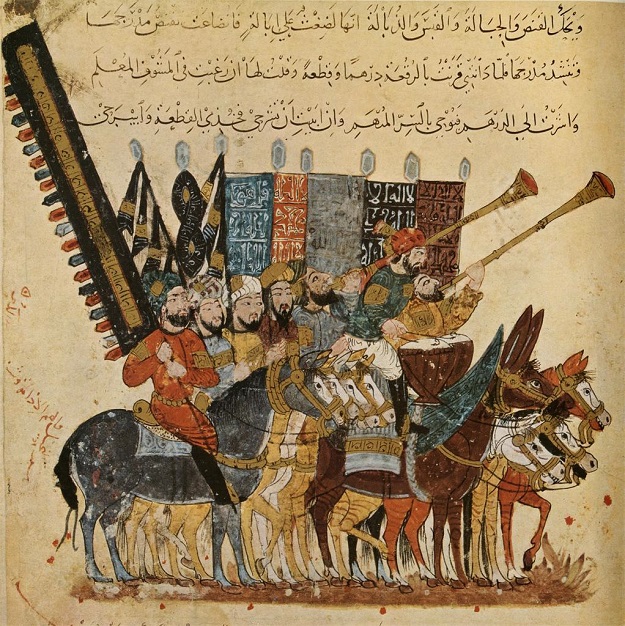

Extra: in relation to the above image, I went browsing through The Assemblies of al-Hariri to see if I could find any mention of this fine brown mule. I did not, but I did find mention of a mule belong to Abu Dulâmeh (a poet, and the son of an emancipated black slave). The mule is apparently renowned throughout Arabic literature for his dirty tricks, and is mentioned in this rather fantastic selection of insults:

0 thou, meaner than Hâdir, and more ill-omened than

Kâshir, and more cowardly

than Sâfir, and flightier than

Tâmir, hurlest thou at me thy own shame, and thrustest

thy knife into my honour, while thou knowest that thou

art more contemptible than Kulmeh, and more vicious

than the mule of Abu Dulâmeh, and more indecent than

a fart in company, and more out of place than a bug in

a perfume box.

The translation notes in the copy I read explain the line thus:

A compendium of all possible depravities [and impossible to translate decently], but to be guessed at by fox-hunters who remember what Reynard is said to do when hard-pressed by the hounds; excusable in his case as a means of self-defence, but in the mule sheer wanton mischief at the cost of harmless passers-by.

There is also mention of Abu Dulâmeh having immortalised his mule, but what that means will probably have to be the subject of another post entirely. “Sheer wanton mischief at the cost of harmless passers-by” is absolutely a phrase to be associated with mules and I think I need it on a t-shirt!

I know very little about mules in history (actually nothing), but I was intrigued by both the kind, Internet-passerby with the story and your research to go along with this. When I first read the title of this post I thought it was going to be the story of Balaam and the donkey in the Bible. But I should have known–a donkey is not a mule. 🙂